JANUARY

19 January

Archibald Stevenson the Brigade’s first Honorary Treasurer died on voyage to South Africa.

FEBRUARY

14 February

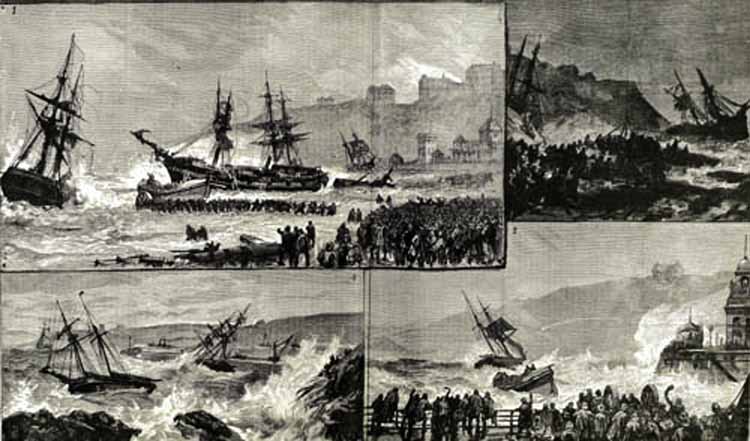

The Ann and the Reaper came ashore and both crews were rescued by the Brigade.

19 February

The Gazette publishes a criticism of its own coverage.

Honour to Whom Honour is Due

To the Editor of the Shields Daily Gazette

Sir,—ln your issue of Tuesday an account of the gallant rescue effected by the South Shields Volunteer Life Brigade appears wherein certain statements are made which are not substantiated by the facts of the case. The members the South Shields Life Brigade were reported to have seen vessel approaching the harbour about 7 p.m. Allow me to state that pilots on the look-out at the Beacon were the first to see the lights of the two vessels stranded behind, or to the south of the South Pier, and not the coastguard or brigade men as stated your report. Pilots had to give the alarm to the pier police and coastguard at least half-an-hour after the vessels stranded, and had South Shields lifeboats been permitted to be launched without the Castor's guns giving the alarm to the whole town, the crews of both vessels would have been landed, and the vaunted services of the pet life brigade would not have been required as in olden times. Would it not well when a report is given to the public of South Shields and the world at large, that the parties who keep the brightest look out for casualties, other assistance, should receive at least a portion of the honour and the credit due to anyone who is willing to risk his own life and limb to save his fellow-creatures from a watery grave.—Yours, &c.

Jacob Harrison, Pilot

South Shields, Feb. 17, 1881.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 19 February 1881

MARCH

2 March

The evidence given in this salvage case refers to the Brigade.

Salvage Claim

At the North Shields Police Court, to-day —before Ald. Shotton, Messrs R. W. Surtees and Thos. Jackson-—William Fountain, master of the Hartlepool brig Cicero, was sued for a certain sum, not exceeding- £200, for salvage services rendered to the Cicero, whilst in a dangerous position near the Tyne on the 15th February last, by the owners of the steam-tug Ganges. Mr Maples (Newcastle) appeared for Joseph Lawson, complainant, and Mr Roche (Sunderland) for the captain of the Cicero. Wm. McCoull, master the tug Ganges, said that on the morning of the 15th February he went over the bar. There had been a heavy storm on the previous night and a strong sea prevailed. The wind was light from the SE by E. He saw the Cicero coming towards the piers. She was in a very dangerous position. He spoke to the master and asked him were he was going to, to which came the reply “We are going Shields.'' Mr McCoull then said you cannot get to Shields that way, you are going behind the south pier. They were a very little way from the stones and broken water, and in sight of two wrecks which had got behind the Pier the night before. He asked £10 for towing the Cicero into safety, but the captain would only promise him "foy" money. The Cicero continuing to drift towards the broken water, the captain called the tug get hold of the towline, saying, "Get hold, of the rope, for God's sake, as soon as possible." Whilst getting hold of the rope the tug herself ran great risk. When the Cicero was got safely into the Tyne the captain refused to pay anything. Cross-examined by Mr Roche: He would swear that he did not put his tug in such a position as to make the Cicero drift inshore. Several other witnesses were then called to corroborate the captain. A member of the South Shields Coastguard, who was on the pier that morning was next called. He saw the Cicero, and she was heading right for the land. She would "been ashore in five minute had not the tug hold of her. He ordered the life brigade men who had been duty from the previous night, to get the apparatus ready.—Captain Fountain, of the Cicero, denied in toto the statements of the previous witnesses, and he declared that his vessel was not endangered in any way. She was wholly his property, and was not insured. The mate of the Cicero then gave evidence to corroborate the captain. He admitted that the tug people said “Be sharp or you will be ashore," but he believed they made a row to terrorize the crew into making a bargain, (Laughter)

The Bench decided that salvage services had been rendered. They awarded £10 to plaintiff, and might have given more if that sum had not been mentioned.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 2 March 1881

3 March 1881

South Shields

The Brigade is on “look out” duty.

Since yesterday morning the weather has been very stormy. During yesterday the wind blew strong from S and SE, and last night it increased to a gale. The sea along the coast rose as the gale increased, and by night-fall the out-look seawards presented a most foreboding appearance. Several vessels ran for and entered the harbour in safety. The pilots were on the lookout, and the members of the Volunteer Life Brigade mustered for duty. The latter continued in the Watch House all night, The wind finally settled into a south-east gale, and the sea rose and broke heavily upon the bar, and washed high over the Tyne piers.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 4 March 1881

4 March

The gale and snowstorm continue with unabated fury. The members the South Shields Volunteer Life Brigade remained on duty last night, and kept strict look-out, but no lights were seen off the harbour. The officers of the brigade who remained during the night were Captain Cottew, Deputy-Captain Whitelaw, and Mr S. Malcolm (secretary.) Captain Mabane was on duty during the day, and until 10 pm.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 5 March 1881

11 March 1881

The Gazette publishes a prize winning essay, which includes a brief history of the Brigade.

The History and Future Development of South Shields

Prize Essay

In Dec., 1865, a few gentlemen at a private meeting came to the conclusion that a Life Brigade should be formed South Shields similar to that at Tynemouth. On the 15th Jan., 1866, meeting was held the Town Hall, under the presidency of the Mayor (Mr T. Moffett), and at which there were present Ald. James, Mr J. Crisp, Mr S. Malcolm, Mr Geo. Lyall, Dr Denham, and others. It was resolved to establish a brigade, and in the course of the next fortnight nearly 130 persons had enrolled themselves as members. The first drill took place at the South Pier, on Feb 17th, 1866, under the command of Mr Byrne, the coastguard. Although the Tynemouth brigade had attended several wrecks, and fired rockets over vessels in distress, they could not boast of having brought anyone ashore and the honour of saving the first life was reserved for the South Shields men, who, at the stranding of the schooner Tenterden, of Sunderland, in April, 1866, were able to land seven individuals by means of the rocket apparatus. Amongst the persons rescued were a woman and child. The incident of their rescue forms the subject of one of the pictures hanging on the walls of the brigade house. After the experience of one winter it became evident that a shelter must be provided for the men, and appeal for this object was made to the public. A watch house was built, consisting of two-thirds of the present room and the porch outside. The next year berths and other accommodation for shipwrecked crews were provided. In 1875 the main room was lengthened 18ft., and a look-out was added above, from which good view seaward is obtained. Appended is an account of the services rendered at shipwrecks by the brigade:-

Date |

No. Of Vessels |

Persons Landed by Rocket Apparatus |

1866 |

2 |

11 |

1867 |

3 |

19 |

1868 |

6 |

24 |

1870 |

2 |

16 |

1871 |

1 |

3 |

1873 |

1 |

2 |

1874 |

2 |

10 |

1876 |

2 |

27 |

1878 |

1 |

8 |

|

19 |

120 |

In addition to the above 26 wrecks were attended and assistance rendered.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 11 March 1881

APRIL

18 April

An original copy of this article is on display in the Watch House.

The South Shields Life Brigade

Under the heading " A Noble Band," a special correspondent writes to the Daily Telegraph: —Down upon the white space of sands on the south side of the mouth of the river Tyne, with the low grey cliffs behind, and two immensely long breakwaters, which answer to the name of piers, shooting into the waters of the German Ocean in front, stands a solid, handsome edifice of one storey, surmounted by a species of watch tower. The sand is all about it, heaped up in strange, irregular banks and hillocks by the east and south east winds, which often blow with terrible fury over the leagues of sea beyond. Of all structures, ancient and modern, which overlook our English waters, I cannot imagine one that should excite more earnest interest and sympathy than this building. It is the watch-house of the South Shields Volunteer Life Brigade, erected by public subscription, dedicated to the most sacred type of humanity—an asylum for shipwrecked men rescued by a band of salvors who risk their lives for the sake of their fellow-creatures without reward, from impulses so unselfish that it is difficult for any man who knows the dangers of the sea to speak of them without emotion. As the story I am about to relate will show, it was my fortune to inspect this house on an occasion when its usefulness and the heroism of the men who are attached to it were illustrated with an emphasis that will furnish me with a lasting memory.

I had arrived at South Shields at half-past six in the evening. There was strong wind blowing from the south-east, the sky was black, and the moan of the high surf could be heard a long while before -the sea was in sight. I knew that a heavy gale was expected; indeed, the barometer had surely indicated a storm of wind, and having learned that a bright look-out was being kept at the Life Brigade Watch-house, I quitted the town and walk in the direction of the sands. I felt the force of the wind when I was near the sea, and made my way with difficulty against it, striking ankle-deep into the sand that from time to time was blown like fine smoke, penetrating the clothes and drifting in to the very skin. The bitter cold of the wind pained my face like the teeth of a saw, and the sea under the black sky, as far as the eye could pierce, was like a surface of snow, the height and fury of the breakers being indicated by the thunderous note of falling waters. The windows of the watch-house stood out in yellow squares against the blackness, and directed me. The labour of reaching the building was exhausting work, and heartily glad was I to find myself under the lee of it at last, out of the fury of the gale. I knocked and entered. On closing the door, and looking around me, I found myself in a tolerably spacious room, lighted by a handsome chandelier fed with oil, the clear lustre of which was brightly reflected in the varnished panelling and the richly-stained boarding under the roof. A number of men stood at the windows looking on to the sea, or were grouped about the table. A few of them were dressed in ordinary costumes, but most them wore a kind of uniform, consisting of blue guernseys, with red collars and cuffs, white belts, and water proof light grey helmet-shaped caps. These were some of the members of the Volunteer Life Brigade—most them men of good social position—who had left their homes in order to station themselves in their watch-house ready to rescue life should a ship miss the mouth of the Tyne, and drive ashore. Owing to the construction of the roof of the house, and to the comparative bareness of the great room in which I stood, the roaring of the wind sounded with terrible distinctness, and the crash of the surf came with it like the firing of guns in a heavy action at sea. My eye was immediately attracted by a number of names emblazoned in gold, or pointed in brilliant colours, upon short boards, and hung around the large apartment. On asking what they signified, I was told that they were the name-boards of some of me vessels which had been wrecked off South Shields, the preservation of the crews of which the Volunteer Life Brigade had taken apart. I read aloud a few of these names, and as I pronounced them a commentary of statistics rendered wildly impressive by the bellowing of gale and sea without was given by one of the members. "Eagle—eighteen men and a boy saved." "Union—Eighteen men and boy." "Scylla —All hands lost." "Tyne—All hands lost." "Blenheim —All hands saved but one." “Impulse—All saved." “Frisia—All drowned but two." And so on. It seemed an odd fancy to collect these name-boards of wrecked ships and decorate the room with them; yet no other kind of embellishment could have been more picturesque, more suggestive, more pathetic. They were just such memorial tablets as sailors would put up to ships that had foundered; very simple, but most movingly expressive, each one text upon which the imagination might muse for hours to the beating of the cruel sea upon the shore.

The house, as I have said, directly faced the ocean, and the front portion of the interior of the structure consisted of one large room. At the back, however, were several compartments. The first I entered was a roomy chamber, containing six sleeping berths or bunks, screened by red curtains on brass rods. A closet in this room was filled with blankets ready for immediate use. In the left-hand corner was the surgery, and separated from this the bathroom, in which I took notice of a large locker full of coats and trousers and other articles of attire, intended to replace the streaming clothes of shipwrecked men after they had | been bathed and warmed. It would be unnecessary to describe the hundred little conveniences which the noble foresight of these lifesavers had assembled in their watch-house. Everything was exquisitely clean, and the maritime character of the building was prettily heightened by a model here and there of a ship, by pictures illustrating shipwreck and the preservation of life, and by rocket-sticks and other articles of that kind. “What I see greatly impresses me," said l; "and I can only wonder that the fame of a service so unselfish and heroic as this should not have extended beyond the district How many members have you?” “One hundred." “You are all volunteers?" “Yes. When the weather is stormy—as it is to-night—a body of us come here and keep watch, ready to fire the life-lines and give other help should vessels drive ashore?" "How do you meet your expenses?" "By appeals to the public; the Board of Trade help us a little, but not much. Last year they gave us £40 in all. Our expenditure last year was nearly £130 and our receipts £119—so the balance was against us. Perhaps we were to blame for this, and I'll tell you how. A performance was given at the Theatre Royal for the benefit of the widows and children of some pilots who were drowned at sea. Half the proceeds was offered to us, but our committee thought it would be better for the whole of the money to go to the widows and orphans. If a mistake was made, it was on the right side. Yet we sometimes feel the want of money. Our uniform caps are very old, and some of the members have not any caps to wear." Are there any other volunteer brigades like yours on the coast?" “There are four this way and two on the Cumberland side. The movement is limited to Cullercoats, Tynemouth, this town, and Sunderland; and on the other side to Whitehaven and Workington."

At this point a vessel came ashore. After describing the scene and the rescue of the crew, the correspondent proceeds:—lf ever real heroism was shewn it was on that night. If ever manful, unselfish courage needs an illustration no more need be done than to point to these South Shields Volunteer Lifesavers, and to their brother volunteers on the coast to the north and south of the mouth of the Tyne, and those who keep the same noble vigils at Whitehaven and Workington. The example shown by these volunteers ought to be known, that it may stand chance of being imitated. As yet but six towns in all Great Britain—four of which lie close together— can boast of one of the worthiest and most honourable confederacies which humanity ever prompted mankind to perform. The lifeboat service and the useful courageous coastguards have long needed the supplement of such a service that which I saw at work on that black and dreadful night at South Shields, and everybody ought to lend hand to aid the extension all around the coast of those volunteer brigades, with their excellent watch-houses and superb discipline, whose existence sheds a lustre upon the half dozen English towns which originated them, and sets a splendid example of willing dutifulness.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 18 April 1881

MAY

JUNE

JULY

16 July

The Annual Meeting took place.

South Shields Volunteer Life Brigade

THE ANNUAL MEETING will be held in the Watch House, on Monday first, July 18th, at 7 30p.m.

S. MALCOLM, Hon. Sec.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 16 July 1881

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

23 September

The Brigade is on duty due to unsettled weather.

South Shields

The weather on the coast still remains unsettled. There was a temporary cessation of the rainfall last evening, but towards midnight it re-commenced. The wind veered round to the north-east, and freshened to almost gale. The members of the South Shields Volunteer Life Brigade were on duty, but fortunately their services were not required. The life-boat crews were also in readiness to render assistance in case of emergency. The sea ran about nine feet high on the bar, and, the darkness of the night being intense, the approach of vessels to the harbour was a matter attended with considerable risk. Between nine and ten o'clock last night a screw-steamer was observed by the men in the watch tower at the South Pier to be making for the harbour. Her progress was watched with much anxiety, the vessel was considered to be much too near the end of the pier to weather it. So great was the alarm, indeed, that the brigadesmen were mustered for duty. It was then seen that the vessel was clear, and she proceeded into the river in safety. This was the most exciting scene of the night, the other vessels which took the harbour managing to keep the proper channel.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 23 September 1881

OCTOBER

14 October

The Atlantic came ashore and the crew were rescued by the Brigade. The scene attracted a large crowd.

The gale continued for several days and received extensive coverage in the local press..

Scene on the South Pier Last Night

Hundreds of persons visited the South Pier, last night, and alter climbing over the heaps of sand which had gathered by the Coastguard house, stood watching the drifting wreck, amidst showers of spray. Through the darkness, the schooner, fast going to pieces, could be seen bumping and rolling about as monstrous waves, white with foam, leaped upon her. The members of the South Shields Brigade were still on duty in goodly numbers, exemplifying the homely Shields motto of "Always Ready." Lights were anxiously looked far, but none beyond those the trawlers and tugs already mentioned were seen. At low water, just before midnight, the crew of the unfortunate vessel, assisted by some of the younger brigadesmen, boarded her by means of a ladder, and brought ashore the bulk of the stores, clothing, and other effects. Excepting the captain and mate, the crew were all boys. Judging by their faces they seemed to think lightly of their experiences of the da y. As the night wore on the sky cleared and the moon shone out, illuminating the whole scene. The sea was yet enormously high, and huge black walls of water, tinged on the surface with foam and spray, continued to roll on the beach and around the pier end. As the wind finally settled down into the west, the brigadesmen relinquished their watch at half-past one.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 15 October 1881

16 October

The Gale

South Shields

The weather was fine, but cold, during the whole of yesterday. The pier and sands at South Shields were visited thousands of persons, many of whom came from a distance. The wreck of the Norwegian schooner Atlantic was an object of special interest. Men were busily engaged in dismantling her, and saving as much as possible, both of stores and cargo. The sea continued rough, and fleet of vessels, which had been detained the storm, sailed from the Tyne. There were also several arrivals, and many of the vessels bore traces of having suffered by their exposure to the storm.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 17 October 1881

19 October

The Bertha went ashore on the Herd Sand , to the south of the Fish Pier. The crew were rescued by the lifeboat, Tom Perry.

20 October

The Gales

Another Storm on the North-East Coast

Last Night at the South Pier

Just as the saddening influence upon our minds, wrought by the experiences of Friday last, was becoming less, and the limit of the harrowing list "of disasters caused by that memorable storm was being reached, we found ourselves on Wednesday threatened by another gale, and last night engaging the full fury of another storm. Happily a lengthy warning had been given, and all were prepared. The stormy weather of the previous night shewed little signs of mending throughout yesterday. A strong breeze continued to blow from the south-east, and in the afternoon there were a succession of squalls. About seven o'clock last evening there was indeed a calm, but it only lasted for brief period, and was succeeded by a very heavy breeze. Gaining strength rapidly, by half-past eight a thorough south-east gale was blowing, which has continued without abatement since, accompanied by pelting rain. Towards midnight the wind backed a little to the eastwards, and as daylight broke it returned again to its old quarter. Some say a little more to the southward, but if so the alteration, was very small indeed. As is always the case during bad weather the South Pier was again the rendezvous sightseers, sea-faring persons, and the noble-hearted life-brigadesmen. In the earlier part of the night, however, there was little to satisfy the curious beyond the familiar sight of an expanse of white foam, backed by an impenetrable veil of darkness; and this view was only obtainable from odd corners where shelter from the driving rain and blinding sand could not always be obtained. The chief cover for spectators was the lee of the Brigade House, and here a group of persons pressed closely upon each other for shelter, many amusing themselves by flattening their noses against the windows and staring at the brigadesmen, who were smoking or otherwise whiling away the time inside. The wind was piping away terribly by ten o'clock, and the red glare of Tynemouth Light was blurred by driving mist. The barometer then stood at 30, having only fallen 2-10ths since the morning. It remained at that figure until well on in the morning, when it again fell a trifle. Several lights were seen from time to time in the offing, and were watched anxiously. For several hours a steamer continued to} appear off the end of the pier, each journey whistling loudly and burning a flareup. It was concluded that she was a foreigner, and wanted a pilot. She was not seen again after midnight. Several other steamers' whistles were heard at different hours, but at all times lights were not discernible, owing to the thickness of the atmosphere over the water. Shortly before one o'clock, a steamer's lights were again discovered off the pier, and amongst the coastguard and brigadesmen there was some excitement, as she was supposed to be in a rather dangerous position. The lights, however, disappeared, she evidently putting to sea again. At a quarter to two o'clock, at which time the storm seemed to gain additional energy, a steamer was sighted, and after a struggle passed safely into the Narrows, in what was termed by onlookers as—grand style. Several other lights, principally the side lights of sailing vessels, were caught sight of, and as soon lost again, away to the southward.

The Mishap to the Iron Crown

The most exciting incident, however, occurred about half-an-hour after midnight. About this hour there were several members in the watch tower. It appears to be customary for the watchers, on sighting lights, not to trouble their comrades waiting below, unless there is apparent danger. When they do not fear harm to vessel, the fact is conveyed by simply calling to those below. The intimation of the proximity of the Iron Crown, however, was made by several watchers apparently trying to get down below, by jumping in a body from the top to the bottom of the circular staircase. Simultaneously, the coastguardsmen thundered with their knuckles on the window. Instantly all hands were to their feet. Slumberers were aroused by indiscriminate digs on the body. In a few seconds a crowd of stalwart fellows, tying on their storm caps as they ran, made a pell-mell rush out of doors. A sailing vessel's starboard light, from amidst the mass of white foam flickered across the water. In addition, huge flare ups fired on the forecastle illuminated the surrounding water. As soon as the state of matters was realized, there was a hearty shout of “coats off, lads." In the twinkling of an eye, a dozen fellows, stripped to the guernseys, gathered behind the rocket van, through the crevices of which show the rays of light from a lantern within, and it was rapidly receding along the dark pier. The moving figures disappeared to view. The movement was so quickly made that the onlookers seemed bewildered, and it was some moments before any one followed. Hardly a moment more had elapsed, when the scene was illuminated by flash of fire-like lightning. Then came the boom of cannon, and the vessel's distress was signalled from the Spanish Battery. The Iron Crown seemed undoubtedly to be drifting on to the sands behind the Pier. She appeared, at first, to be quite half-a-mile to the southward of the Pier, but gradually drifting towards the gearing. The brigadesmen with the van had only got a little way beyond the iron landing stage, when all lights from the vessel disappeared. “She’s gone," was whispered round, but still the van was pushed on. In another moment a blue light was burned, sending a blinding glare around, but not a vestige of the Iron Crown was discerned, The blue light burned low, and yet the vessel did not reappear. Presently another red glare burst over the water. Two guns were now fired from the Battery, and then a continuous thread of fire rose into the air, followed by the bursting of rocket. The cry of " There's another ashore" was then raised, but the puzzled brigadesmen upon whom the spray leaping up the sides of the masonry, and high into the air, fell in masses, then guessed what had become of the Iron Cross. She had drifted, with the narrowest of shaves, past the South Pier end, and across the harbour in towards Tynemouth Haven, The distressed vessel continued to fire rockets until the lights on the North Pier told that the Northumbrians were going to the rescue. There was much anxiety manifested owing to the great length of time the Tynemouth men worked at the vessel. Her huge form could be seen lifting up and down across the blue light, and everyone was greatly concerned. At one time a fear was expressed that the unfortunate vessel might be a German emigrant ship, and that she might be crowded with passengers. The scene on the North Pier was intently watched until towards three o'clock, when half-a-dozen leading brigadesmen determined to ease their anxiety if possible. A suggestion that some definite information might possibly be gained the Coble Landing was acted upon by a party immediately undertaking a journey thither, through the pelting storm. Fortunately full explanation of the state of matters was received from a number of lifeboatmen; and the enquirers soon retraced their steps and eventually relieved the minds of their fellow watchers.

The storm continued with unabated severity, and many persons who came down to the pier upon hearing the alarm guns, returned home. Lights continued to come in view until daylight, and there were several rushes down the pier in anticipation of work. Fortunately, vessels managed to keep out of harm. When dawn appeared, the state of the sea reminded one the scene now nearly twelve months since. The wind had freshened if anything, and the outlook to windward was most threatening. Everyone eagerly scanned the north side for a sight of the Iron Crown, and much surprise was evinced at her size and, more than all, at her extremely narrow escape.

The Pilots Drowned at Shields

Up to noon to-day the bodies of John Ramsey and Thomas Tindle, pilots, who were drowned last Friday afternoon, had not been recovered, A movement is on foot for getting up a concert for the benefit of the widows and orphans,

The Wrecks at South Shields

The galliot Bertha, which stranded on the Herd Sands, at South Shields, on Wednesday night, is still aground, no attempt to tow her off having been possible owing to the storm. The vessel, however, still remains intact, and is riding head to sea. The wreck of the three-masted schooner Atlantic, which was driven ashore at the South Pier, last Friday's gale, will be sold by auction to-day.

The South Shields Lifeboat Slipway

Owing to the range the harbour, consequent upon the storm, the South Shields lifeboat slipway is covered every tide with sand, stones, and chalk, and there is great difficulty launching the lifeboat. The ways are cleared at low water each day, but still the accumulations occur with every flood tide, The lifeboat Northumberland, which got ashore last Friday, will be “ housed" at South Shields lifeboat station to-day, and the Tyne, of South Shields, will be sent to take her place at North Shields. The Tom Perry will be kept at South Shields, so that there will be one boat ready at each side of the harbour in any case of emergency.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 21 October 1881

22 October 1881

South Shields

As was generally anticipated yesterday morning, the gale has continued without the slightest sign of abatement, and is now raging with undiminished force. Certainly there was diminution in the rain fall during yesterday, but as evening approached, the downpour commenced again, and continued from seven o'clock till considerably after midnight. At no previous period of the gale was the rainfall worse than last evening. The wind still came from the old quarter—ESE, varying to SE— and notwithstanding the deluging rain and spray, the sand was raised into the air and driven over the South Pier, and on across the harbour in perfect clouds. On the pier flags near the stone yard of the Commissioners the sand had gathered into heaps and belts, in many places several feet high. These deposits were rounded and faced by the wind with all the perfection of snowdrifts. Making headway on to the pier through the darkness, with rain, spray, and sand driving against the face, was a truly horrible undertaking, even to those protected by oilskin and so’-wester. Yet, despite this, scores of persons fought and struggled on, with no more to shield them from the fury of the storm than the ordinary garb, until the lee of the Brigade House was gained. The crowd at this spot was larger by far, and remained watching seawards till a much later hour, than on any previous evening. Some, more venturesome than others, made short excursions along the pier, struggling over further heaps of sand, which extended for fully hundred yards beyond the Watch House. Opposite this point the wind literally dug the sand up by hundred weights, and hurled it across the outer pier wall in sheets. As far as the eye could penetrate into the gloom, the water was a mass of seething foam. Extending into the white expanse the dark masonry of the pier could be traced. Huge masses of white water could be seen leaping across it, and climbing about the black timbers of the gearing at the extremity, with awful grandeur. Vessels lights were less frequently seen, but the onlookers were occasionally rewarded by seeing a steamer, which had tossed about outside, safely travel up the Narrows.

The Life Brigadesmen mustered in goodly numbers, and their exceedingly comfortable house was well tenanted. As the small hours of the morning approached, the men did not disappear as sometimes happens, but an excellent watch was maintained until daybreak. Many of the members were then in their third night's watch, but they all stuck to their task in most praiseworthy style. The excitement of the previous night was not again experienced, lights, as already stated, being few. Not one sailing vessel was reported. The weather was exceptionally bad from midnight until about four o'clock, after which the rain clouds broke somewhat. The view from the look-out tower was most discouraging. The noise of the falling rain and howling wind was dismal for the watchers who sat hour after hour in darkness and silence eagerly peering through the windows. Just before dawn huge cloud banks rose from the horizon, and the sky was again overcast. The look-out men were twice somewhat startled by flashes of lightning bursting from the clouds the distance. One very brilliant display of forked lightning was observed to windward about o'clock. When day broke glasses were turned to Tynemouth Pier for the unfortunate Iron Crown, It was now discovered that she had gone to pieces before the night's threshing, and that her hull lay in two pieces beneath the Battery Cliffs, About seven o'clock those Brigadesmen who had watched through the night were relieved by fresh hands.

The Missing Tug Samson

Nameboard Washed Up

About half-past six o'clock this morning, the Coastguardsman, Frederick Jaggers, observed a piece of timber lying on the sands immediately behind the South Pier, On turning it over proved to be a piece of a tug's bulwark with the letters “ S.A." on one end, painted yellow. The plank had been broken off partly through the "A." This is said undoubtedly to be a portion of the ill-fated tug Samson, which was caught in the hurricane on Friday week.

Mr Piper, chief of the coastguards Seaham Harbour, reports to-day the finding of a boat marked Samson, a little to the south of the port. It is supposed to belong to the tug Samson.

The Bodies of the Two Missing Pilots Picked up

Last night, Wm. Duncan picked up the body of a man on the sands at the Low Lights, North Shields. It was afterwards identified as that of Thomas Tindle, pilot, 29, living in Edith Street, South Shields, who was drowned in the gale of Friday last. On the same night the body of man was picked up on the Black Middens. According to the description it appeared to be that of a man 55 years of age, 5 feet 11 inches in height, bald on top of head, grey hair on back of head, stout build, dressed in grey serge trousers, grey stockings, sea boots, and a white long flannel. The skull is broken, and the arms are very much cut. The body, which was conveyed to the dead house, and has since been identified as that of John Ramsey, pilot, Baring Street. An inquest will be held.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 22 October 1881

24 October

The Gales

Continued Storms in the North Sea

Tynemouth

Since our last impression the storm has raged with unrelented fury. When darkness set in Saturday, several steamers and sailing ships had made the harbour. About 5 o'clock three-masted schooner was watched with much concern as she crossed the bar, great seas were tossing her about like a cork. From that time to daybreak, on Sunday, no vessels made for the port. All Saturday afternoon thousands of visitors fringed the sea banks. Over 5,000 persons travelled by the ordinary and special trains on the North-Eastern and Blyth and Tyne Railway watch the storm, During the afternoon, Mr I. L. Sankey, accompanied by large party, visited the Tynemouth Brigade House, where they witnessed the storm and were shown the interior and the appliances for saving life. Mr Moody was much impressed with what he saw.

A Serious Accident

About o'clock young man named Edwd. Straker, belonging to South Shields, along with his brother, were picking their way among the rocks below the Spanish Battery, when an alarming accident happened. Edward Straker, who, by the way, was in the rear of brother, fell head foremost into a cavity between some rocks; his legs were seen sticking in the air. The elder brother once went to his brother's assistance. He was taken out insensible and conveyed the Brigade House. Dr Bramwell was sent for. Having been put into a warm bath Straker was placed in one of the beds for a while. He was sent home to South Shields in a cab. Dr Bramwell pronounced the injury received concussion of the brain. Straker's face was also much disfigured by the fall. He assigns peculiar circumstances as the cause of his falling. Observing large piece of fat pork floating in a pool of water among the rocks he mistook it for the mangled remains of body washing ashore. The sight sickened him, and he fell over.

At midnight in the look-out house steadfast watch was kept upon the sea. At two o'clock in a morning a most tremendous sea was roaring with all its might. In the open it was almost impossible to face the violent blasts of wind. A retreat to the look-out house was therefore the desirable mode of watching for inbound vessels. The wind was dead east for considerable time, chopping alternately to the north and south. Not a vessel made the harbour till daylight, when a scene of awful grandeur was everywhere visible. Not a sail was to be seen wherever the eye could scan nothing but a tumult of breakers and angry seas, Broad daylight was a relief to the thoroughly exhausted Brigadesmen. Brigade duty had now occupied over one hundred and twenty hours. As a large influx of visitors was expected the Brigade House was swept and trimmed up for continuation of duty. Knots of hardy lifeboatmen remained behind, many of them having only snatched a few hours' sleep during whole five days.

At half-past ten o'clock screw-steamer was seen making for the harbour. Her progress was carefully watched across the bar, where she shipped tremendous heavy seas. Keeping a magnificent course she relieved the tension of anxious minds by safely getting through. The steamer proved to be the John Ormston. Another steamer made for the Tyne about twelve. Alarm was widespread among the thousands of people assembled on the shore, as the vessel was seen burrowing her way through the seas.

A few more vessels arrived during the remaining part of the day.

The visitors to Tynemouth yesterday were unprecedently numerous. Additional the sixteen ordinary trains from Newcastle to Tynemouth ten specials were put on, all packed, even to the van. It is calculated that over 6.000 persons travelled by the North-Eastern line alone. This large number was further swelled by the thousands who came down in the Tyne General Ferry Company's boats. Blyth and Tyne Railway was also under severe pressure. All the booking windows at the Central Station were used for the traffic to Tynemouth.

On Sunday afternoon a party of salvors picked up the large figure washed from the stem of the Iron Crown. It was placed in a cart and taken to the Battery Bank. It measures fully six feet in length. The arms were off, but they have since been found, and are now lying in the Brigade House. Shortly after this find, a collection was made by a party of Brigadesmen among the assembled crowd on the Battery Bank. £9 3s 5d was collected. It will be added to the Widow and Orphans' Fund. Fewer Brigadesmen attended last night watch. A fine body Cullercoats lifeboatmen were present.

The wall at Clifford's Fort, North Shields, has been greatly damaged by the heavy seas breaking against it, and the stones have been carried long distance westwards, many of them being scattered upon the ways of the Northumberland lifeboat house.

South Shields

To pick up the thread of our narrative of the gale, it may be mentioned that, with the dawn on Saturday morning, four days of the weather recently allotted to North Britain by the New York Bureau, had been wiped off. For a period of ninety hours the gale had been blowing with incessant fury, and there appeared only remote chance of improvement. The Americans, it will be remembered, supplemented the prediction referred to, by wiring that a further disturbance would visit the North-British coasts from the 23rd to the 25th. To this friendly warning there was an addition, which at the time seemed painfully ironical, notifying that dangerous energy would be developed. Towards mid-day on Saturday, the wind lulled great deal, and only came away in slight squalls. This continuing till evening, impression became general that the gale was at last dying away, and that the prospective blow, with the promised dangerous energy, would prove miss. Unhappily, however, the very reverse transpired. The barometer, which had remained steady at slightly below 30, began to fall and the wind rapidly backed eastwards. The squalls gradually became heavier, the wind coming away terrific gusts, accompanied by heavy rain, and occasionally hail. Between eight and nine o'clock the gale was far stronger than at any period during the previous three days, in fact, it was perfect repetition of the memorable 28th of October, 1880.

Marketing on Saturday Night

The renewal of the storm not only troubled seafaring minds, bet made matters seriously uncomfortable for tradesmen and their Saturday night customers. The furious wind and driving rain cleared the streets, and, comparatively speaking, depopulated the Market Place. Stall keepers here conducted their businesses under most trying circumstances. In many instances, not only awnings, but the entire stalls, with the stock-in-trade, seemed imminent danger of demolition. The ferry steamers from the north side had not their wonted Saturday night freights, the passengers crossing river being reduced to most ordinary numbers.

During Saturday afternoon, several vessels, after severe struggles, successfully effected an entrance to tin harbour, and helped to swell the already crowded fleet moored at the tiers. Between four, and five o'clock Norwegian barque was seen trying to make the harbour, and eventually caused immense excitement by hairbreath escapes. At one time she was in great danger of going ashore on the south side, and shortly afterwards along the verge of the Black Middens was watched with bated breath. Owing to most skilful banking, however, she eventually cleared the dangers and got safely into port. It afterwards transpired that she was half full of water—a fact which rendered her management extremely difficult. Just before noon another piece of the tag Samson's bulwarks washed ashore, and by fitting it into the piece picked up the morning, two other letters of the name were made perfect.

Shower of Hats

During the afternoon hundreds of visitors got down to the water's edge, and remained viewing the storm. At one time a number of them ventured some distance along the pier. At each squall, hats parted company with their owners, and alighted on the water over the Herd Sand. During one heavy puff of wind, the flight of truant tiles is described as resembling a lot of crows. The utmost consternation prevailed amongst the hatless ones, who stood with hands on head as if they expected their crops of hair to follow next. "It is an ill-wind that blows nobody good." Fortunately an individual turned up, accompanied by a retriever. A labourer, seemingly, is not more worthy of his hire than a retriever dog is. The owner of the dog having first struck a bargain, the praiseworthy quadruped, was set to work, and for some time did good business in landing “at threepence each."

The Noble Band

The Watch House of the South Shields Brigade had been well tenanted all day, but when the gale shewed such renewed energy, after dusk there was a grand muster. The room had a remarkably cheerful and animated appearance. The seedy look of the morning had been removed by thorough tidying up, and the floor had been treated to a liberal supply of saw dust, which considerably added to comfort by absorbing the drippings from boots and oilskins. A thorough air of "business" pervaded the whole camp. There was a constant opening the door, and expressions of welcome to new arrivals who, one after the other, would pause on the threshold to scrutinize the assembly from within their weatherproof casings, and give significant shakings of the head as to the state of affairs out of doors, Pulling off storm cap and oilskin followed, and there stood specimens of physique which it was impossible not to admire. The pick the brigade were there, and at midnight the call of the muster roll gave forty-two hands. The freshness of spirits and undaunted air exhibited by the men, although the bulk of them were then entering upon their fourth consecutive nights' watch, was simply marvellous.

Outside the building, the bluff coastguard man had the whole of the place himself. There was no crowd of spectators pushing and edging one another for shelter. It was evident that either the weather was a 'wee bit too strong, or that the novelty had worn off. The guardsman stowed himself under the lee of the house and sucked his clay in solitude, occasionally cheering his soul by peeping through the window the scene within. The weather increased hourly, and as the floodtide made, the condition of the sea was simply appalling. Supper had just been got over, when the alarming condition of things out of doors, and the poor prospect of saving crew from such sea, should any vessel go against the pier, was eagerly discussed. Nothing could be done, certainly, beyond keeping a vigilant watch, and being in the utmost state of readiness. It was suggested that a little drill within doors might greatly conduce the latter, especially as there were several young hands present, The suggestion was immediately acted upon, and in a brief space of time, a rocket frame, in which nestled a huge rocket, was fixed in the room. Then portions of drill as to fixing the rocket, fastening the whip, sighting, and other matters was gone through under the chief of the coastguard (Mr Hart) The process of landing crews with the breeches buoy was also exhibited by means of model tackle, extending from end to end of the room. The utmost interest was raised by this incident, and for an hour afterwards groups of men were gathered here and there engaged in knot tying. Amongst some of them the affair evolved itself into almost prize competition, when, it is needless to add, old seafaring hands shewed some dexterous work.

About four o’clock a change had come over the scene. The fact that it was Sunday morning had not been overlooked. Cards, dominoes, and other attractions had been scrupulously stowed away. The drilling had been over some hours, and there was nothing for but smoking and reading. The storm raged with unabated fury. The wind shook the building to its foundations, and the roar of the rain and hail upon the wood work was terrible. Why not have some music?—was whispered round. Standing against one of the centre tables was a piece of furniture, not unlike a well-used old oak chest, and looking as if it had been up ended, so as to increase the surface of the table. "Here's the harmonium, if anyone will give us a tune"—said a member. The instrument had not been used for some time, and it was feared that owing to damp species of asthma might have affected the pipes, and that whatever sound came from within might not, after all, be much better than the piping of the storm. Another prominent brigadesman, however, soon dispelled this doubt by playing the instrument, and showing that it was both sound in wind and limb. A Moody and Sankey hymn book was next discovered, and instantly the performer was surrounded by group of men. The scene which followed was most impressive, and will not readily be effaced from the memories of those who witnessed it. Every one sang heartily and with feeling, and for a good hour the combined voices of the stalwart fellows brought out the beauties of the revivalist hymns. The flood of harmony reached the watch tower and brought down to join in the chorus all possible hands belonging to the watch. Members who had stowed themselves away for a nap, crawled from their hidings one by one, and likewise joined in. The singing was most appropriately concluded by the well-known hymn, from the service for the distressed at sea—" Eternal Father strong to save"—being thrice repeated.

From eve to dawn not a light was seen. After daybreak, a body of men made a journey along the beach, when another piece of the Samson's name board was found. This piece completed the first four letters of the unfortunate tug's name. Considerable excitement occurred about 8 o'clock, when several hands reported having seen a vessel off Souter Point. Two hands were most emphatic upon the point that a vessel was riding off Souter. It was proved eventually that nothing was there but an idea existed that the appearance of the vessel was due to a mirage, a not unfrequent occurrence with easterly winds. The watch was early relieved by fresh hands. The terrible state of the sea when seen by daylight was the subject of much comment, and the horizon was eagerly scanned by numerous glasses. There was nothing, however, but a vast waste of water, running mountains high, and topping as far from shore as could be brought within the range of a powerful telescope.

The brigadesmen and coastguard hands frequently discussed the question of, the absence of proper protection along the north side of the pier. It was pointed out that railings have been lying in the Commissioners' yard for a considerable time, ready for putting up, but nothing has been done. Should a vessel strike the pier end, at high water during a heavy sea, brigadesmen would be in imminent danger of being washed overboard wholesale.

The weather yesterday moderated considerably towards the afternoon. Several vessels made the harbour in safety, but lights again disappeared late on after dark. There was another watch, which, despite the fact that it was the fifth night running, was well attended. Several steamers entered the harbour, but no sailing vessels.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 24 October 1881

NOVEMBER

26 November

The George Clarke and the Ida both stranded on the south side of the South Pier. The Brigade rescued both crews.

DECEMBER

1 December

The debate over the lights at the entrance to the harbour was rekindled by recent events

The Entrance to the Tyne

The gathering of the South Shields Life Brigade, last night, following after the stranding of the two vessels at the back of the South Pier, on Saturday, directs attention to the dangers attending navigation on this coast and the means in force to rob shipwreck of its worst peril. The last two years, especially that now closing, have been specially stormy on this coast. They have, however, passed over with comparatively slight loss of life as compared with the extent of the shipping entering and leaving the river. Where loss of life has taken place it has been due to causes from which the safest harbour entrances are not exempt. We are not sure that this remark applies in its full force to the loss of property. It is difficult always to account for accidents, the responsibility for which is divided between the state of the atmosphere, the quality and position of the harbour lights, the safety of the entrance, and the character of the navigation. At least five vessels within the year have come to grief without sufficient cause in the state of the weather to account for their loss, total or partial. One night in February last year two sailing vessels landed at the back of the South Pier, the one mistaking the harbour entrance, and the other following the first as guide. Last Saturday, other two vessels did the same. The George Clark mistook the entrance through some misapprehension of lights and the Ida followed, both beaching themselves on the sand. The fine vessel Iron Crown was lost a few weeks ago because the captain had lost his way, and could not pick out the lights which should have guided him into the harbour.

These circumstances would seem to support the allegation, often heard, that the lights at the entrance to the Tyne are not so efficient as they might be made. It is well for nonprofessional people to approach such a subject as this with the greatest caution, and it is well also to note that plenty of testimony could be found in favour of the efficiency of the present arrangement. Still, some weight must be given to the testimony on the other side, which is considerable, and seems, as we have said, to be strengthened by such facts as those we have mentioned. The subject, our readers know, has not escaped the attention of the River Commissioners and the Trinity House. It is, of course, a great mistake to have one authority for the river channel and another for lighting the entrance. It is a relic of the old evil state of things, when a Corporation in Newcastle were allowed to thwart the development of river improvement, and levy tolls which were spent for corporation and not for river purposes. And the arrangement has the same evil consequences. Expense is multiplied, improvements are delayed, and efficiency is, of course, lessened. But we have the dual arrangement, and must make the best of it till we get a better. Some time ago the Commissioners, through their engineer, submitted a scheme where the high and low lights would have been brought into harmony with the altered channel of the river. The Trinity House, after a somewhat farcical inquiry, decided that it was better not to interfere with these lights till the piers were finished. But they agreed to a modified form of another proposal by Mr Messent, namely, to place a revolving light on the end of the of the Fish Pier, the Commissioners to make the foundation and the Trinity House to supply and maintain the light. This resolution remains with the Commissioners to carry out. There is thus definiteness on at least one point. It is to be hoped no time will lost in carrying this resolution into effect. Lately, the want most strongly felt has been some guide the harbour entrance, not so much a guide after the entrance is passed. We say lately this has been so, but the wreck of the Mary and certain others which Lave gone ashore on the sands south of the Fish Pier since, are evidence, on the other hand, either that the observation of the navigators is imperfect, or the lights not so definite as they should be. It not admissible to doubt that the erection of a revolving light on the Fish Pier would add safety to the passage up the river, even if it did not make it impossible, in ordinary clear weather, to mistake the lights of King Street, South Shields, for the harbour. The question, however, arises whether this is enough. We are met at once with the argument that an undue multiplication of lights means simply an increase of confusion. But it is equally legitimate to reply that no lights at all are a little worse. We disclaim any wish to add to the Babel of amateur engineering any suggestion of ours, but common sense does suggest that the best guide the river mouth would surely be a bold light which there could no mistaking on each pier end. Navigators know their own business best, of course. However this may be, one or two things are clear, first that this new proposed revolving light will give a distinctness to the lights not now possessed by them, that the proposal of the Commissioners' engineer to put the leading lights, so to speak, in line with the channel, leaving nothing to the judgment and nothing to conjecture, commends itself to reason, and thirdly, that it could do no one any harm to have the Tynemouth light strengthened to show a longer distance out to sea. Whatever is done should be done quickly.

But when all these things are done, something will still remain to complete the precautions desirable for the safety of life and property the mouth of the Tyne. Arrangements must be made whereby, on the stormiest night, vessels entering the harbour should have the benefit of pilotage. By the present system strangers are deprived of this assistance at the very time, and amidst the very circumstances when it is needed most. Provision must be made in the shape of a steamer or steamers capable of living whenever it is possible to cross the bar, and by means of which pilots may be taken off to vessels in want of their guidance. Who are to provide these craft may be a matter for discussion; such must be provided if we are to make good our claim as a harbour refuge. In the circumstances, the pilots can hardly be expected to bear the original cost where pilotage is merely voluntary. But it is the interest of the Commissioners, as representing the port, that every means should be taken to increase the numbers who frequent it, and it ought not to be considered a heavy matter for such a body provide the facilities required.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 2 December 1881

1 December

The Annual Supper took place in the Watch House.

6 December

The masters of the George Clarke and the Ida both state that they could not see the harbour lights.

The Lights at the Tyne Entrance

In view of the discussion as to the lights at the mouth of the Tyne, it may be interesting to print depositions of the captains of the two vessels, the George Clark and the Ida, which went ashore ten days ago, the back the South Pier.

Report of Edward White, master of the brig George Clarke, of South Shields,248 tons, from Boulogne, Nov. 24, for the Tyne (with 150 tons coprolites):—On the 26th, at 7 p.m., tide being high water, weather stormy, wind S, blowing a gale, with a high sea, deponent was keeping his vessel close in to fetch the South Pier. It was very dark and thick, with rain, and deponent could see neither Souter nor Tynemouth Light till close to the pier to clear it. Deponent had therefore to starboard his helm and run the vessel on the beach to save the crew and property. Deponent passed Whitby about 1 p.m., and saw nothing after that he could make out distinctly; he steered NNW 1/2 W from Whitby; the weather was then fine, and the vessel under all plain sail. About 5 p.m., it commenced to blow and rain, and all sail was reduced to two topsails and foresails.

Report of Henry Gibbs master of the ketch Ida, of Ipswich, 136 tons, from Ipswich, Nov. 24,at 2 p.m., for the Tyre (220 tons burnt ore) :- On the 26 ult., at 7 30 p.m., tide high water, weather stormy, wind SSE, a gale with high sea, the vessel being SE by S from Tynemouth Light, under small sail , steering NW by W, deponent saw two lights, which he took be the leading lights into the harbour, He could not see the lights on the north pier, and changed his course to W to enter the harbour, and saw a pier on the lee, which deponent took to be the north pier, but which proved to be the south pier. As soon as deponent discovered his mistake he put the helm down, but the vessel missed stays. He then filled en the vessel again, but she refused stays the second time, drove ashore. The lights which deponent took to be the harbour lights were the lights shown by the life brigade to illuminate the vessel George Clarke, which had stranded about half hour before the Ida.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 6 December 1881

23 December

The vessel has not been identified.

A Vessel in Danger at South Shields

Last night, during the thick fog, the coastguard at the South Pier heard voices shouting for assistance. Officers Hart and Ashton, accompanied by W. Wilson, a member of the Volunteer Life Brigade, once proceeded along the Pier, a work of great danger, the fog being thick that they only dared to move forward along the hand rail of the parapet, and answered the calls. Ashton burned a blue light, but its brightness failed to penetrate the fog. The vessel, which was inside the piers, appeared to be lying near the rubble work between the pier end and the landing stage. Those on board were understood to say that they wanted a tug, but no other information could be gleaned, although the shouting was continued for some time, and the Coastguard were hoarse with bawling out. After a while, no further sound was heard from the vessel, and when the fog lifted, nothing of her could be seen.

Source: Shields Daily Gazette 24 December 1881